An electrical engineering project for the birds

An electrical engineering project for the birds Heading link

When Jeremy Stymacks, Adan Arroyo, and Esam Mohammed were pondering possible projects for the UIC Engineering Expo, the real-world design challenge that is the culmination of the two-semester Senior Design course, Stymacks heard an unusual bird call, one he hadn’t heard before.

“I installed an app called BirdNET on my phone to figure out what I was listening to,” Stymacks said.

BirdNET is a tool developed by Cornell University, a citizen science tool that identifies nearly 1,000 North American and European birds by recording their distinct calls. The app searches its audio database and comes up with a likely match. With curious urbanites, conservationists, biologists, and birders, the app has grown in popularity for its ease of use and accuracy.

Currently, most bird surveying—the tedious counting of where a particular species lives, and how many of that species may be in the region—is conducted by citizen scientists who arm themselves with data sheets, trekking to record and classify the birds they encounter. Perhaps they go out a few times a season, then submit the mostly handwritten sheets. According to Stymacks, many birdwatchers live in urban areas, so large swaths of prime bird habitat in forests and rural regions go unmonitored.

Stymacks, Arroyo, and Mohammed saw an opportunity to automate bird surveying and collect more robust data. Team BirdUP was born.

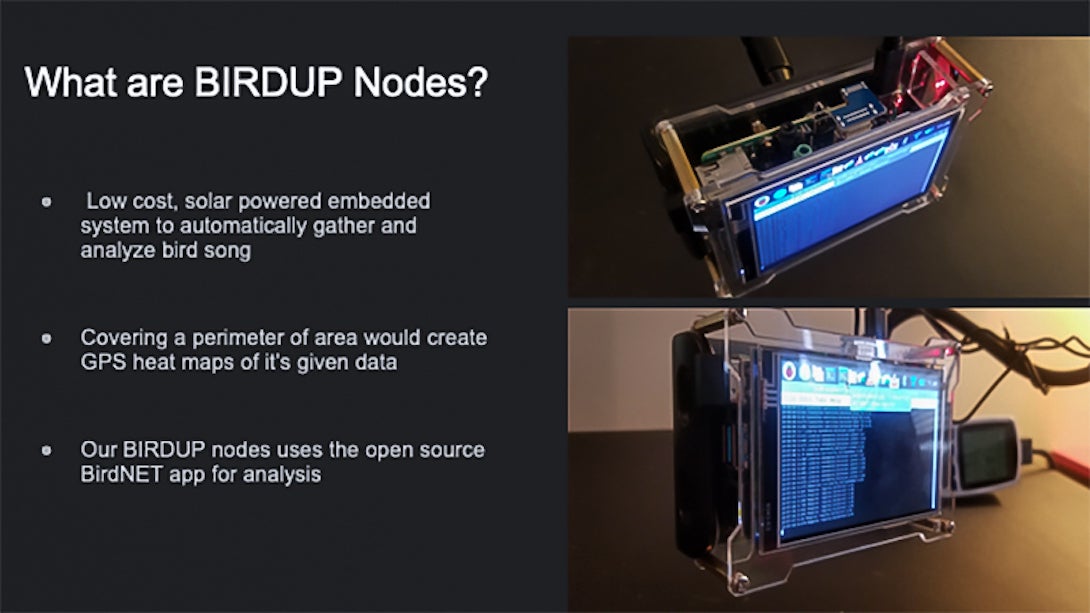

The team designed a Solar Powered BirdNet Node that works in tandem with the BirdNET app. The goal was for the node to be continuously operating, have automated data logging, and classify bird calls via a neural network. The node consists of a 2-gigabyte Raspberry Pi 4, a four-inch touchscreen user interface, and a 12-watt solar panel, with a battery designed to work with the Raspberry Pi.

The node can be left in a secluded area, all the while collecting time-stamped data cached for retrieval, and can be picked up later. Not only will this replace the information now laboriously collected by hand, but the node also will provide a long record of an area as opposed to a single volunteer birder visit, which is merely a snapshot in time.

The UIC team succeeded in achieving four to five hours of run time and believes that a larger solar panel and battery could allow a 24-hour continuous run time. Also, the team would like to add an antenna that would allow several nodes to be connected, daisy-chaining to one another to go deeper into a forest or rural area. BirdUP’s node cost about $150, and the students estimate that the upgraded node would be about $260.

“We might end up finding species we didn’t realize inhabited certain areas,” Stymacks said. “We would like to make a meaningful change; it’s hard to put a price on conservation.”

With habitat destruction the biggest threat facing birds, the Solar Powered BirdNet Node may be just the tool to aid bird preservation. The tool also could be used for other audio-based species monitoring, such as of frogs, bats, and cicadas.

Stymacks worked on software, Mohammed handled data synthesis, and Arroyo focused on power systems.

To learn more about their project, visit their Engineering EXPO page.